Opening the Vault: Declarations of Independence

From Richard Henry Lee’s resolution for independence to the Bicentennial reproductions, these documents highlight the Declaration’s enduring symbol of freedom, liberty, and the pursuit of a more perfect union.

-

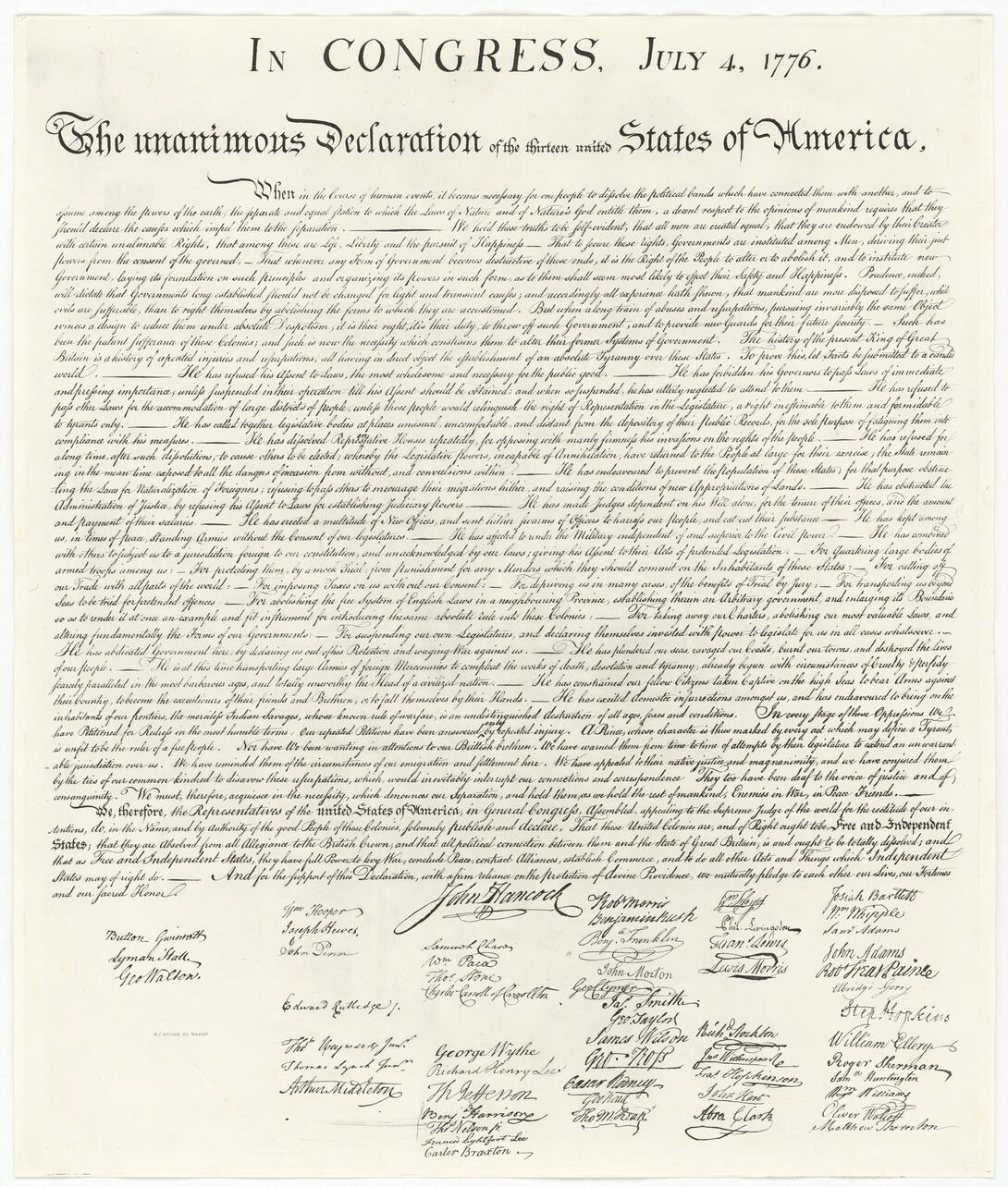

On permanent display in the National Archives Rotunda is the original engrossed Declaration of Independence. Signed by 56 delegates to the Second Continental Congress, it broke ties with Britain and proclaimed that the united colonies are free, independent states. The 250th anniversary of the Declaration will be marked in 2026 and, to celebrate, we are sharing some of the most iconic Declaration of Independence–related treasures held in the National Archives. From Richard Henry Lee’s resolution for independence to the Bicentennial reproductions, these documents highlight the Declaration’s enduring symbol of freedom, liberty, and the pursuit of a more perfect union.

-

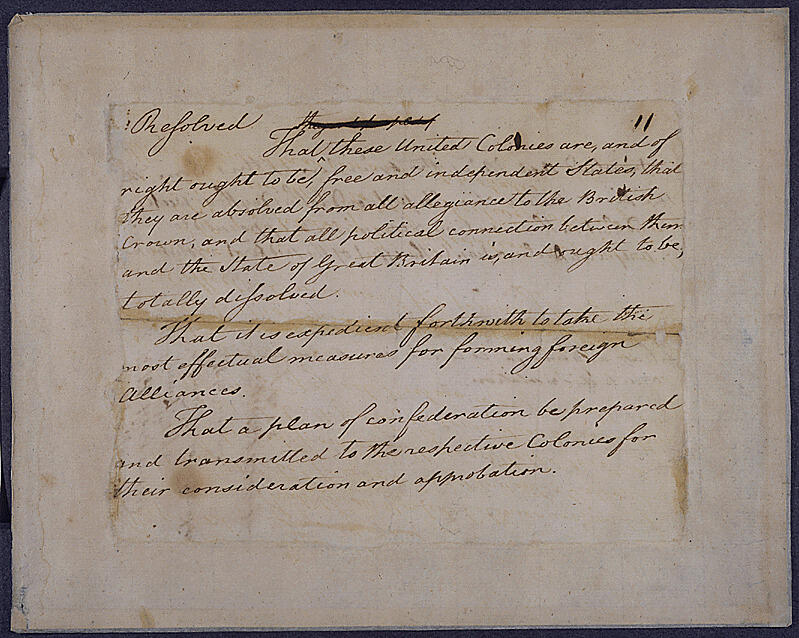

On June 7, 1776, Virginia delegate Richard Henry Lee introduced this resolution, which proposed independence for the American colonies. The Lee Resolution contained three parts: a declaration of independence, a call to form foreign alliances, and of a plan of confederation. On July 2, 1776, the Second Continental Congress adopted the first part of Lee’s resolution, leading to the issuance of the Declaration of Independence and the creation of the United States of America.

Records of the Continental and Confederation Congresses and the Constitutional Convention

-

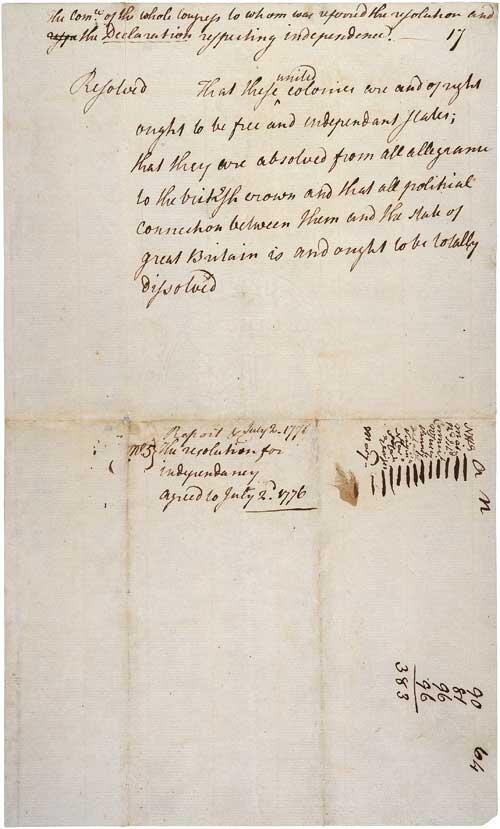

This document records the July 2, 1776, vote in which the Continental Congress agreed to independence. The words of the resolution, originally proposed by Virginia delegate Richard Henry Lee, are echoed in the Declaration of Independence. The bottom half of the document lists the 12 colonies that voted “aye” for independence. A 13th colony, New York, abstained, awaiting approval from the newly elected New York Convention.

Records of the Continental and Confederation Congresses and the Constitutional Convention

-

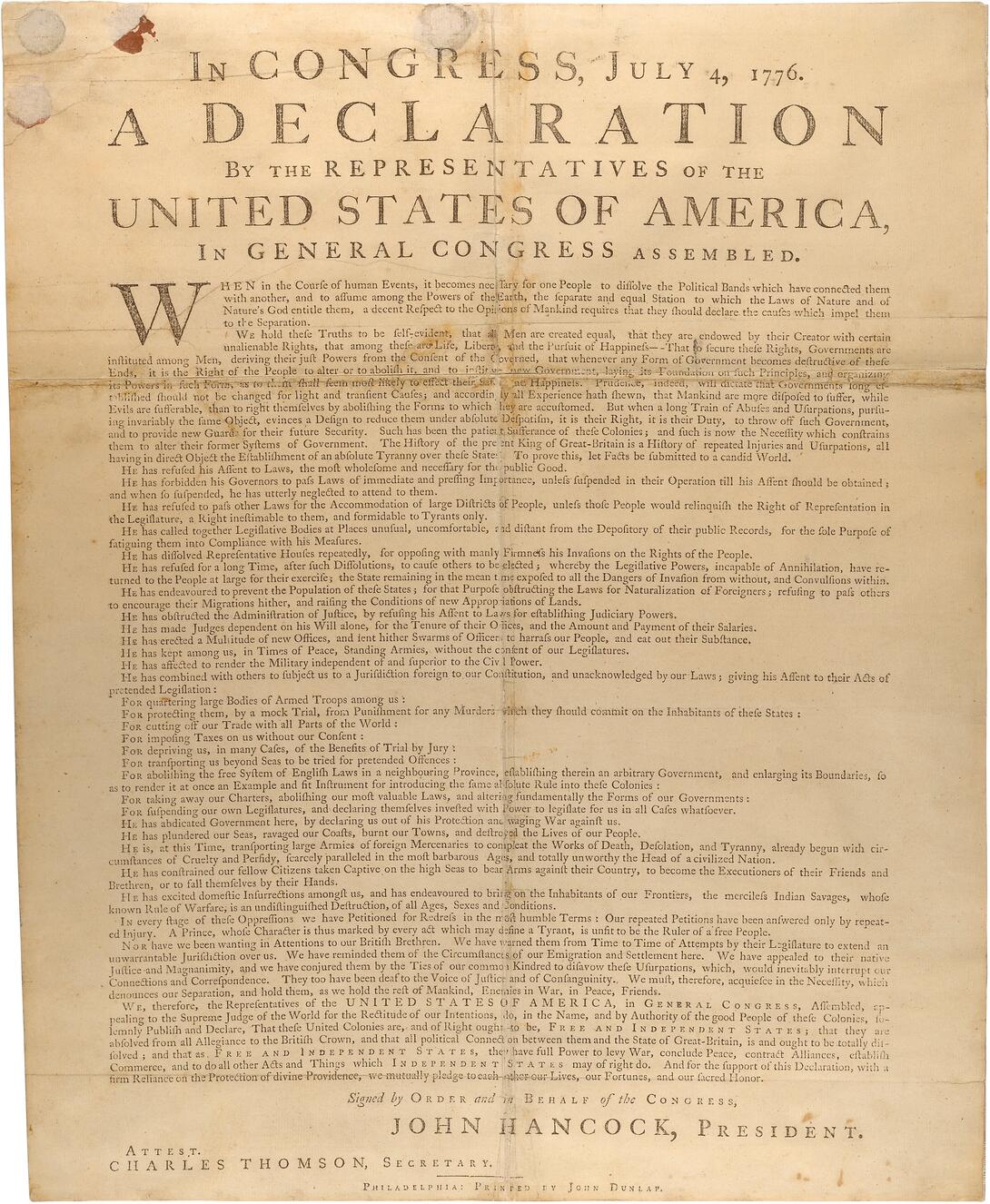

This is the first printing of the Declaration of Independence. After the Second Continental Congress voted for independence, the delegates tasked printer John Dunlap to print about 200 copies of the final text. Working through the afternoon and evening of July 4th and into the 5th, these broadsides were quickly dispatched throughout the country. Now known as the “Dunlap Broadsides,” most of the 26 extant copies belong to institutions in the United States and the United Kingdom. The National Archives has one copy that Secretary of Congress Charles Thomson inserted into the Rough Journal of the Continental Congress in 1776.

Records of the Continental and Confederation Congresses and the Constitutional Convention

Dunlap Broadside, 1776. Records of the Continental and Confederation Congresses and the Constitutional Convention

-

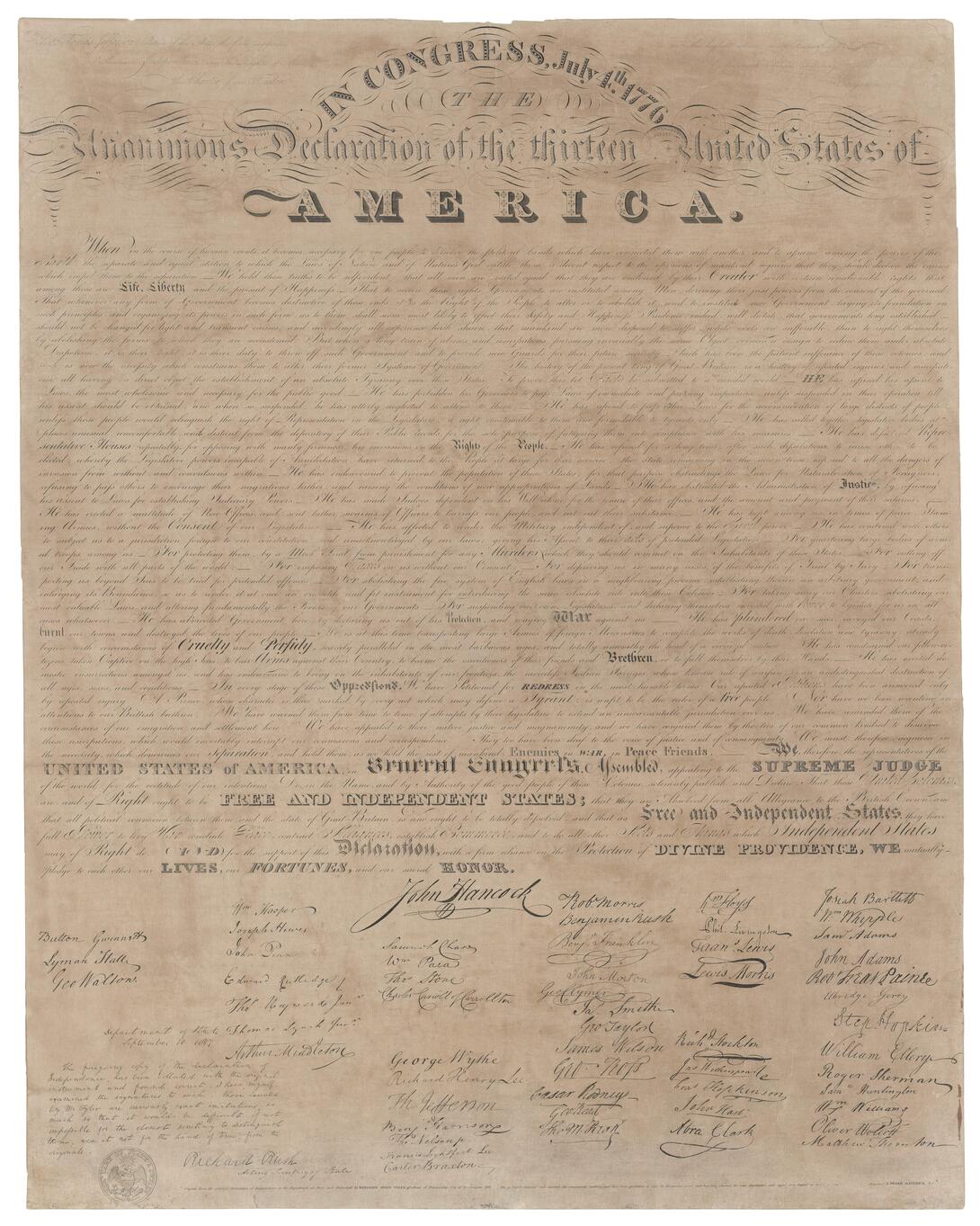

Numerous ceremonial copies of the Declaration of Independence were created in the aftermath of nationalism following the War of 1812. At that time, most signers had either passed away or were quite elderly, and interest in the Declaration was resurfacing. In 1818, engraver Benjamin Tyler published his ceremonial engraving. He dedicated it to the Declaration’s principal author, Thomas Jefferson, and included an attestation by the acting Secretary of State Richard Rush, son of signer Benjamin Rush, that it was a correct copy. The National Park Service estimates that Tyler produced 1,700 copies. The National Archives has one copy of the Tyler Engraving.

National Archives Gift Collection, Richard J. and Anne W. Weichmann Collection

-

During the U.S. Bicentennial in 1976, at the request of the National Archives, master printer Angelo LoVecchio at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing made a printing from William Stone’s 1823 copper engraving plate of the Declaration of Independence. This was the first use of the engraving plate since the 1890s, and the last print run ever made. LoVecchio made six impressions, five of which are held in the National Archives and one in Independence Hall in Philadelphia.

General Records of the Department of State