Thanksgiving: Historical Perspectives

A Harvest Celebration

During the autumn of 1621, at least 90 Wampanoag joined 52 English people at what is now Plymouth, Massachusetts, to mark a successful harvest. It is remembered today as the “First Thanksgiving,” although no one back then used that term. In fact, much of the so-called First Thanksgiving story was created decades and centuries later. As a result, many assumptions about the festival at Plymouth and its connection to Thanksgiving traditions today are based more in fiction than fact. In commemoration of the 400th anniversary of the 1621 harvest celebration, this display explores some lesser-known perspectives on the event and the origins of the federal Thanksgiving holiday.

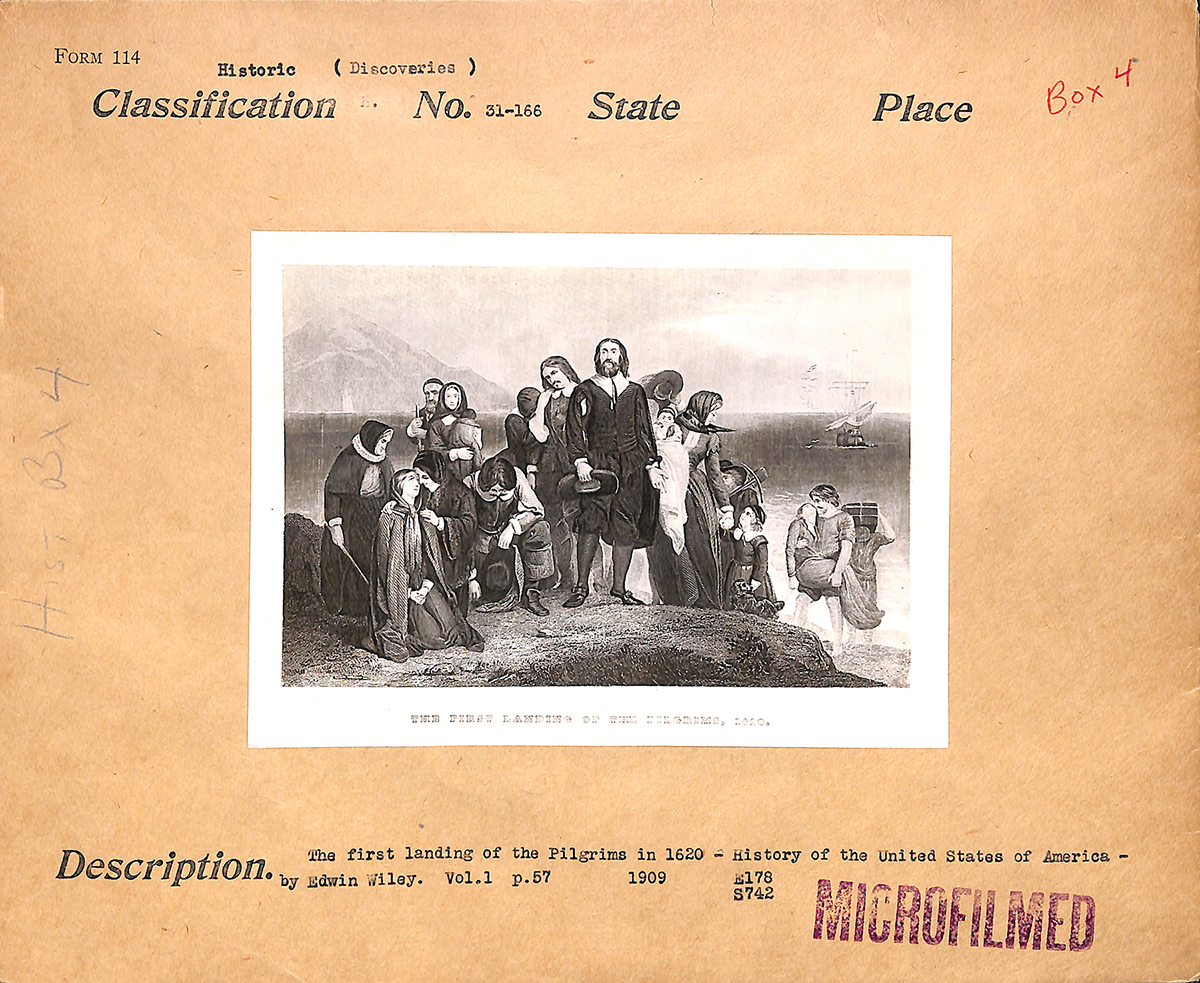

“Classification: Historic ( Discoveries )”

This engraving gives the mistaken impression that the Mayflower voyagers, known today as Pilgrims, discovered unsettled land to colonize. In reality, they came ashore on Wampanoag land. The Pilgrims were not the first Europeans with whom the Wampanoag had contact, and some tribe members already spoke English. Tribal leaders were wary of the English but nevertheless formed an alliance with the colonists for strategic purposes. They also shared knowledge about hunting and planting that saved the Pilgrims from starvation and made the 1621 harvest celebration possible.

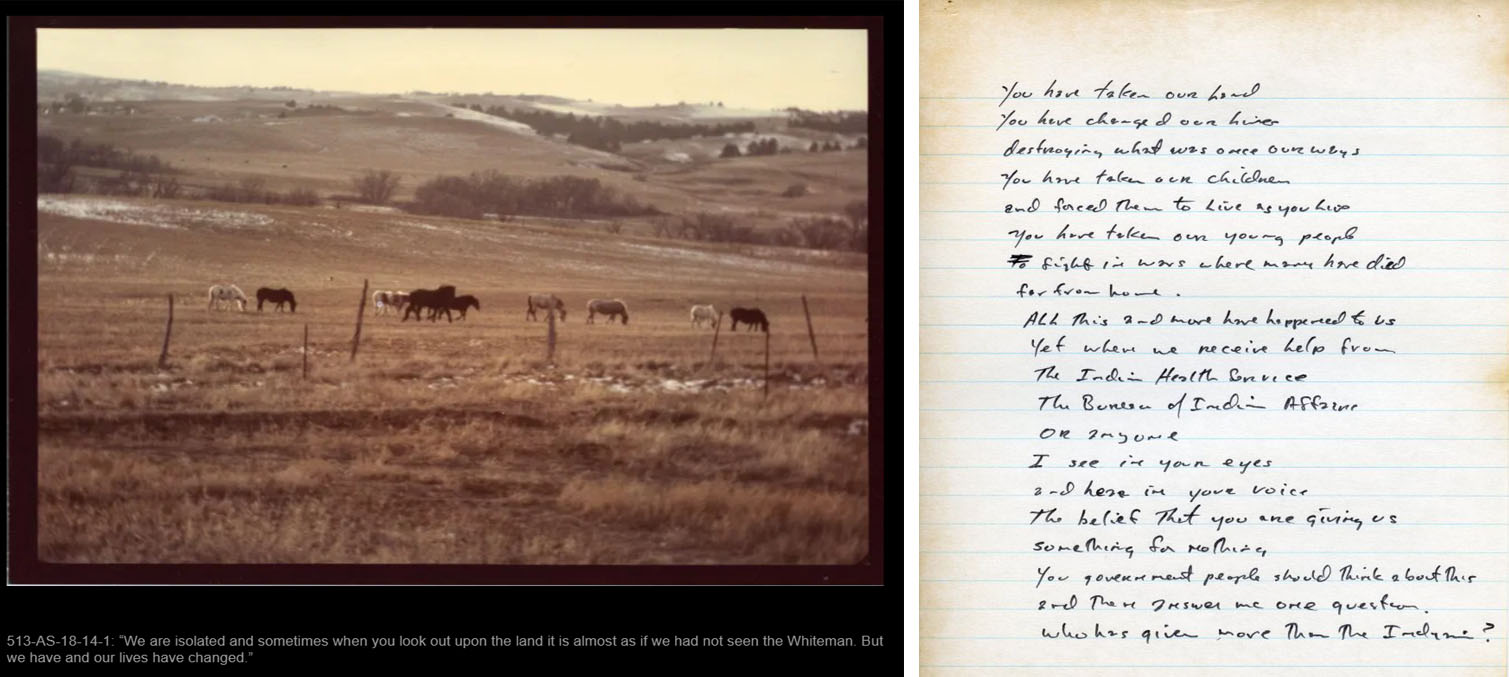

“Who has given more than the Indian?”

The First Thanksgiving story emphasizes a peaceful exchange between the Pilgrims and Wampanoag yet seldom includes a Native American perspective. It also rarely acknowledges that peace was short-lived. Within a generation, war would erupt and the Wampanoag would ultimately lose their political independence and much of their territory. This is one of the reasons why Thanksgiving for some Native Americans is not a celebration but a painful reminder of the devastating impact of European colonization on Indigenous people. This poem attributed to Allan Cayous (Apache/Cahuilla) conveys his personal feelings about how Native Americans are perceived and treated in the United States.

Right: Poem “Who has given more than the Indian?” attributed to Allan Cayous, ca. 1975

National Archives, Records of the Indian Health Service, 1955–79

This photo, caption, and the poem are attributed to Allan Cayous (Apache/Cahuilla), who made a career in the Indian Health Service and served on several national task forces concerned with Native American health matters. While Cayous’s purpose for these works is unknown, he most likely created them during 1970s, when the Native American civil rights movement began to receive greater visibility in the United States. During that decade, the United American Indians of New England organized the first “National Day of Mourning,” an annual protest on Thanksgiving Day in Plymouth that confronts the myth of the First Thanksgiving and the harmful stereotypes about Indigenous people it perpetuates.

A Holiday is Made

Thanksgiving today may have little connection with the Plymouth harvest festival 400 years ago, but it has a long history nevertheless. Originally a regional observance in colonial New England, Thanksgiving began as a solemn affair. Rather than a day of feasting, it was a day for fasting and quiet reflection.

Eventually the states and the federal government proclaimed days of thanksgiving at irregular intervals, but it wasn’t until the mid-19th century, after decades of lobbying by magazine editor Sarah Josepha Hale, that a national Thanksgiving holiday began to be established. As the holiday took root in the United States, so did the need for a distinctly American origin story, and the harvest festival two centuries earlier was remade as the “First Thanksgiving.” While Thanksgiving continues to evolve as each generation of Americans brings new meaning to the day and how it’s celebrated, the tradition of coming together to share a meal and reflect on all that we’re grateful for endures.

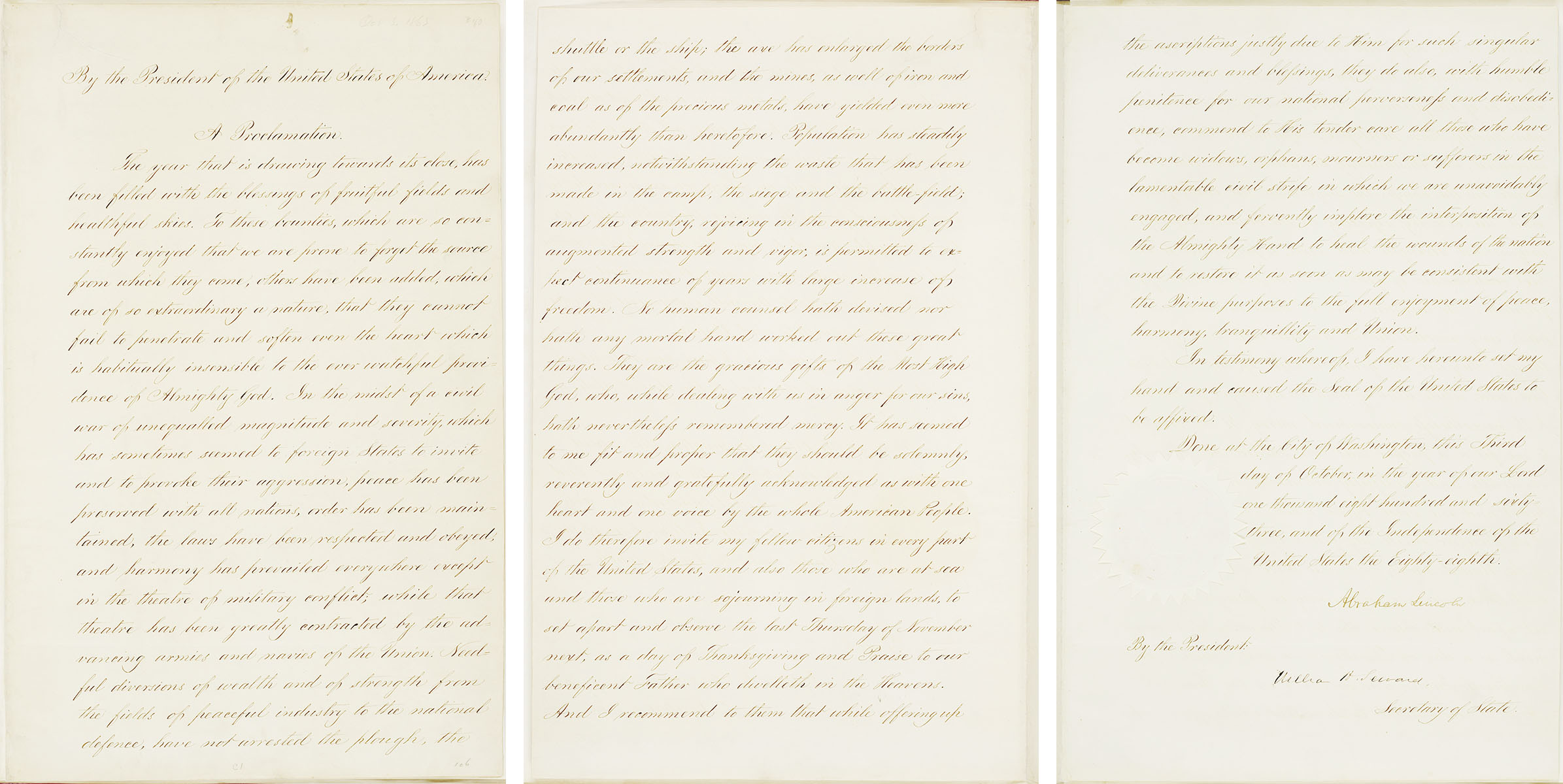

A Presidential Precedent

The federal Thanksgiving holiday has its roots in one of the country’s bitterest moments of division—the Civil War. On October 3, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued this Thanksgiving Day proclamation to help unite a war-weary nation. Lincoln was not the first President to issue a Thanksgiving proclamation, but his order set a precedent to “observe the last Thursday of November next, as a day of Thanksgiving” every year for decades to follow.

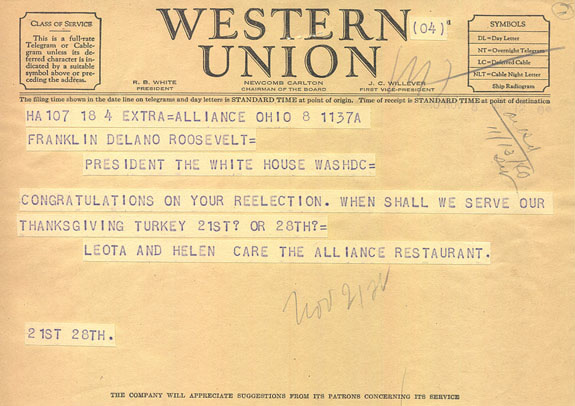

In 1939, the last Thursday in November fell on the last day of the month. Concerned that the shortened holiday shopping season might dampen the nation’s economic recovery from the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued a Presidential Proclamation moving Thanksgiving to the second to last Thursday of November. Sixteen states refused to accept the change, and for the next two years Thanksgiving was celebrated on two different days. To end the confusion, Congress passed a law in 1941 establishing the fourth Thursday in November as the federal Thanksgiving Day holiday.

National Archives, Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum View in National Archives Catalog

Banner Image: Photograph of President Obama, his daughters, and Jihad Douglas at the turkey pardon ceremony, November 25, 2015. National Archives, Barack Obama Presidential Library